The Lost Sutras of Adam

There’s still time for Western Christians to appropriate their history. But not much.

Some seek knowledge for the sake of knowledge: that is curiosity. Others seek knowledge that they themselves be known: that is vanity. But there are still others who seek knowledge in order to serve and edify others, and that is charity.

Bernard of Clairvaux

In 635 AD a new philosophy reached the Chinese capital. Called the “Luminous Teaching,” it promised an ecstatic union with the divine so surprisingly earthy that its primary spiritual competitor—also coming through India—seemed, in comparison, like a mirage. This new teaching was carefully evaluated by the imperial court and tested by learned men; in the end, Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty ruled in its favor: “We find it to be mysteriously spiritual, and of silent operation. Having observed its principal and most essential points, we reached the conclusion that they cover all that is most important in life…This teaching is helpful to all creatures and beneficial to all men, so let it have free course throughout the Empire.”

That teaching, of course, was Christianity.

Christianity reached China no later than the sixth century; it reached the ancient capital (which is a long haul from Jerusalem) not long after that.

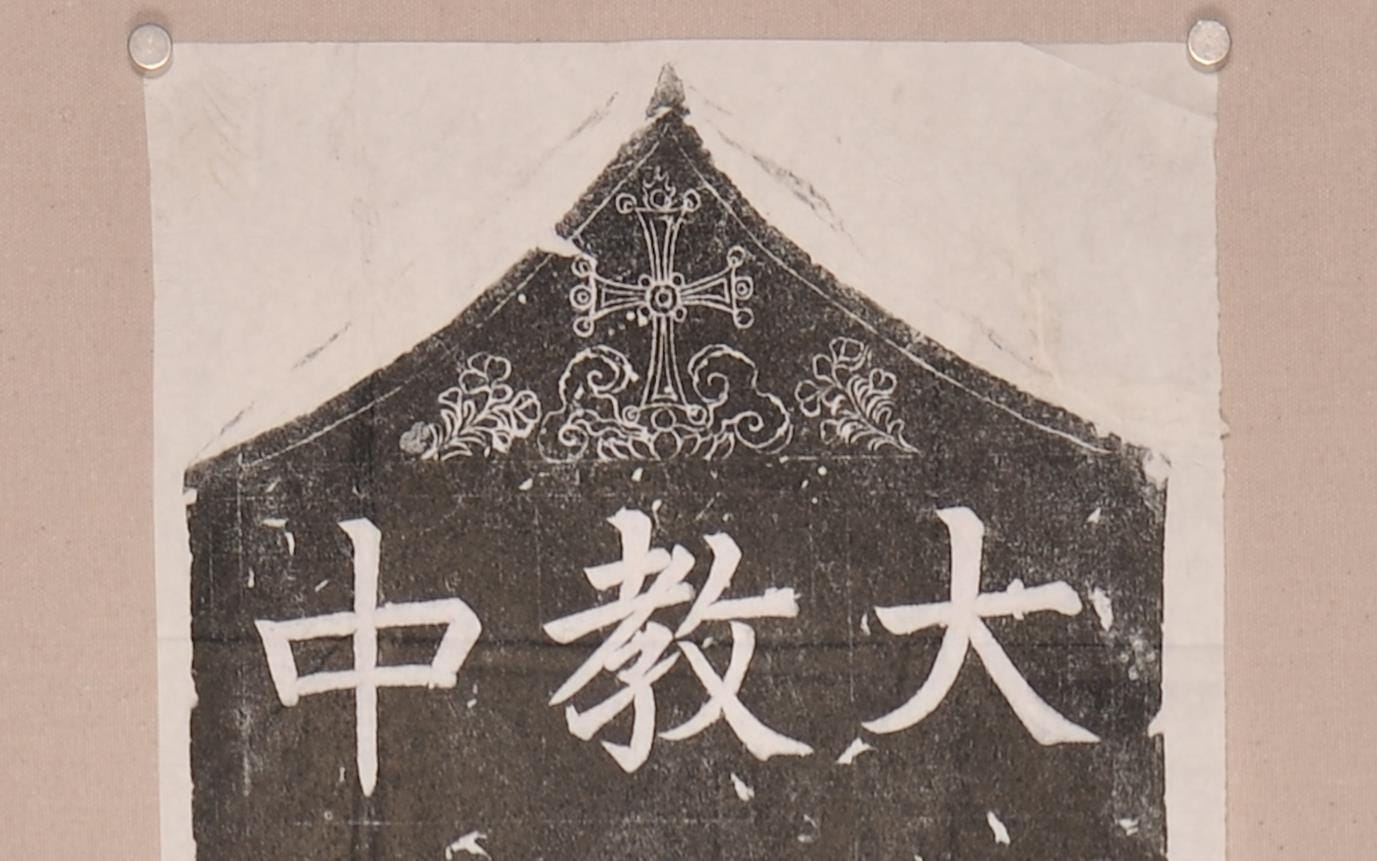

“A virgin gave birth to the Holy One in Syria,” declares an ancient Chinese stele. “He opened the gate of the three constant principles, introducing life and destroying death; he suspended the bright sun to invade the chambers of darkness, and the falsehoods of the devil were thereupon defeated; he set in motion the vessel of mercy by which to ascend to the bright mansions, whereupon rational beings were then released, having thus completed the manifestation of his power, in clear day he ascended to his true station.”

Fascinating, right? Those are unmistakably Buddhist and Taoist categories, conscripted into the proclamation of Jesus. The Gospel was well-received in China; within a few centuries of its arrival there were Christian monasteries scattered across the countryside—there was even a Bishop assigned to Tibet. Those monasteries were appealing targets for persecution when persecution came, which it did in 845 AD. At that time a new emperor made a sincere effort to stamp out Christianity.

Some ancient sources felt he succeeded, but it is not so. The historian Martin Palmer notes, “On the Silk Road, some time prior to 1005, a group of Christians…who dwelt in and around the town of Dunhuang hid their treasured scriptures and paintings in caves in the desert…Thus we can be pretty certain that, more than 150 years after the Great Persecution of 845, Chinese Christians were still meeting, reading their Sutras, and still worshiping.”

Indeed, they were. When Marco Polo arrived in the Middle Ages there were Christian churches present and thriving. They were Nestorians, which we’ll get to in time. For our purposes, it is enough to know that Christianity has been in China longer than Buddhism has been in Japan.

And I cannot help but wonder how much Christianity infiltrated Chinese culture at its roots—less visibly, for now, but no less significantly than it infiltrated Roman culture. Is it still there, like secret seeds, waiting for the time of its revealing?

I think it is.

And not just in China.

This is the fourth part in a series on three trends in Western Christianity—if you missed the other installments, you may want to read parts one, two, and three as well. In this post, I’m going to discuss trend three: After a long and complacent fixation on the present, there is a renewal of interest in Christian history, Patristic theology, and old things in general among Western Christians. That is remarkable because for some 300 years Western Christianity has suffered from a shallow root system—the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox streams no less than the Protestant. And yet that is rapidly changing.

It’s not so much that individual Christians are waking up to the reality of the past.

It’s that God seems to be returning the past to Christianity, and only just in time.

Part I: The Death of the Past

In Viking mythology the end of history is associated with a time of intense darkness, a multi-year winter in which, according to the Eddas, “Black become the sun's beams.”

In the Kalevala, the Finns preserved something similar: “What wonder blocks out the moon / what fog is in the sun's way / that the moon gleams not at all / and the sun shines not at all…The wealth grows chilly / the herds get into a dreadful state / strange to the birds of the air / tiresome to mankind.”

That is a bleak view of the future, but, for our purposes, the relevant issue lies in the opposite direction. That multi-year winter, called the “Fimbulwinter,” is based on a historical event: In 536 AD, multiple volcanic eruptions (plus an unlucky meteor strike) threw so much debris into the atmosphere it caused a year of darkness. It devastated the peoples of the north. The farms were abandoned, the highways were forgotten, and half-built ships were left to rot on the shore. Fifty percent of the Scandinavian population died.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the peoples of the North never forgot those years. When the story of the Fimbulwinter was finally written down, it was in Iceland in the 1200s, which is to say, more than 600 years after the event in question (the Kalevala was written down much later).

Do you see what I’m saying?

In their myths and sagas and oral histories, the medieval Scandinavians were able to remember and locate themselves within more than six centuries of history.

It turns out that’s typical: Cultures steeped in founding myths and oral history can safeguard 500 years of history without breaking a sweat—some go much further back. When the Chronicler of Judah set out to recover the history of Israel, he managed to account for well over a thousand years.

Would you like a recent example? Jesuit missionaries reached Japan in the mid 1500s. A hundred years after that the government began an extremely effective campaign to eradicate Christianity. It did not succeed.

According to the scholar Philip Jenkins, “Even after the overwhelming persecution that uprooted the Japanese church, thousands of ‘hidden Christians,’ kakure kirishitan, somehow maintained their clandestine traditions in remote fishing villages and island communities…One moving documentary from the 1990s, Otaiya, actually allows us to hear very old believers reciting Catholic prayers that first came to the region over four hundred years ago, some in Church Latin and sixteenth-century Portuguese. They pray "Ame Maria karassa binno domisu terikobintsu," a recollection of "Ave Maria gratia plena, dominus tecum, benedicta ..." And they lovingly display a fragment of a silk robe once worn by one of the martyred Fathers.”

Pretty amazing—that is almost exclusively oral transmission and it preserved 400 years of memory.

The point is, in pretty much all times and places people lived with a profound sense of memory. It allowed for what the historian Christopher Lasch calls “historical continuity”—“the sense of belonging to a succession of generations originating in the past and stretching into the future.” Significantly, a sense of historical continuity is a key element in human stability: Communities with a strong sense of historical continuity know who they are, where they’re going, and how they should live.

(Note: “...these oral accounts were as steadfast as our illustrious mountain, and the history that surrounded them soon became fixed as a central focal point in my own personal story,” wrote the scholar Nepia Mahuika. “They told us about who we were descended from, how we arrived here, and how our land was named and populated. This was history.”

No wonder that the Old Testament is filled with exhortations and outright commandments to remember. In fact, in the final years of the kingdom of Judah, the worst of the kings was named Manasseh; he was Hezekiah’s son and the man who—in the Biblical account—brought child sacrifice to Jerusalem. It is intriguing that his name means not “to kill” but “to forget.”)

We Late Moderns don’t have that. We don’t know any history, we have almost no sense of memory, and as a result we are extremely unstable.

I was intrigued by a recent study done by the American Historical Association and Fairleigh Dickinson University. In it, pollsters discovered that “69% of respondents self-identifying as Democrats believe that women generally receive too little historical attention, while fewer than half that number (34%) of Republicans agree,” moreover, “Republicans are up to twice as likely as Democrats to say that religious groups, the Founding Fathers and the military get inadequate historical consideration.”

Here’s the interesting thing about those findings: In 2019 the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation surveyed 41,000 Americans and found that only 27% under the age of 45 could demonstrate a basic knowledge of history in the U.S.—forget about the world! A decade ago, the National Assessment of Educational Progress found that only 18% of 8th graders were proficient in history.

In other words, when asked about the past, people are chiming in on something they have never considered.

“Our age is organized against history,” wrote the prophetic scholar Walter Brueggemann. “There is a deprecation of memory and a ridicule of hope, and that means everything must be held in the now—either an urgent now or an eternal now. Either way, a community rooted in energizing memories and summoned by radical hopes is a curiosity and threat in such a culture…when we suffer from amnesia, every form of serious authority for faith is in question, and we live unauthorized lives of faith and practice unauthorized ministries.”

Yikes.

Brueggemann is right. Our culture doesn’t just devalue history. It hates history to the point that some scholars call our contemporary attitude a “war on the past.”

That attitude is extremely dangerous. According to Tony Judt, one of the great historians of the 20th century: “Of all our contemporary illusions, the most dangerous is the one that underpins and accounts for all the others. And that is the idea that we live in a time without precedent: that what is happening to us is new and irreversible and that the past has nothing to teach us.”

That is well put, and the problem for Christians in the West is that the West’s anti-historical bias has infiltrated the Church.

“On my study door is a cartoon,” wrote the professor Bruce Shelley. “Students who stop to read it often step into my office smiling. It encourages easy conversation. It is a Peanuts strip. Charlie Brown's little sister Sally is writing a theme for school titled, ‘Church History.’ Charlie, who is at her side, notices her introduction, ‘When writing about church history, we have to go back to the very beginning. Our pastor was born in 1930.’”

That about sums it up, and let me remind you: It’s not a Protestant problem. It is a Western problem. In fact, the very conception of the Church as being divided between the Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox streams is itself anti-historical (or, at least, a-historical). It’s not even close to what happened.

I have to say: When I try to explain our culture’s anti-historical bias, I feel like I’m trying to explain nuclear weapons to people who have never seen gunpowder. Our modern empires are not the first anti-historical powers to grace the stage of the world. It’s been done before, a long time ago, and it is extraordinarily effective.

In fact, in being anti-historical, our culture is borrowing a page from the playbook of the great Asian empires of the Middle Ages that all but erased Christianity from several million square miles of the world.

Part II: Imperial Myths

In the late 1200s an aged monk appeared in Rome. The pontiff Honorius IV had but lately died and so many cardinals were assembled to elect his successor. It was good that they were, because those cardinals could interview the monk. His name was Rabban Bar Sauma. He was a Bishop as well as a monk, and (probably) an Onggud Turk. He’d come from near modern-day Beijing in the then Mongol empire at the behest of Kublai Khan to broker an alliance with the other Christian powers of the world.

The dialogues that ensued are fascinating. The cardinals knew little about the Christian presence in the East, and yet Bar Sauma’s responses were so thoroughly Christian he was allowed—on multiple occasions—to serve communion.

(Note: When pressed for his creed, Bar Sauma replied: “I believe in One God, hidden, everlasting, without beginning and without end, Father, and Son, and Holy Spirit: Three Persons, coequal and indivisible; among whom there is none who is first, or last, or young, or old: in Nature they are One, in Persons they are three: the Father is the Begetter, the Son is the Begotten, and the Spirit proceedeth. In the last time one of the Persons of the Royal Trinity, namely the Son, put on the perfect man, Jesus Christ, from Mary the holy virgin; and was united to Him Personally [parsôpâith], and in Him saved (or redeemed) the world. In His Divinity He is eternally of the Father; in His humanity He was born [a Beingl in time of Mary; the union is inseparable and indivisible forever; the union is without mingling, and without mixture, and without compaction. The Son of this union is perfect God and perfect man, two Natures [kêyânin], and two Persons [kênômin]-one parsôpâ [prosopon].”)

Bar Sauma was a monk of the Church of the East, the staggering network of Churches that were cut off from the Patriarchates of the Mediterranean before the Council of Chalcedon.

Because it bears on Trend Three, it’s worth spending a little more time on the strange history of that Church.

It is difficult—especially on first hearing—to grasp the scale and the depth of the Church of the East. For a long time it included the Syro-Malabar churches of India (founded by no less an Apostle than Thomas). It established the great universities of Nisibis and Merv. When Christianity struggled in the sixth century in Europe, many knowledgeable Europeans thought that the traditions of Christianity would be preserved not in Rome or Moscow but in Baghdad. For a long time they were right. Philip Jenkins, trying to adequately describe the historical significance of Christianity in Asia, offers the following mind-boggling paragraph:

“The church operated in multiple languages: in Syriac, Persian, Turkish, Soghdian, and Chinese, but not Latin, which scarcely mattered outside western Europe. To put this geographical achievement in context, we might think of what was happening in contemporary Europe. Before Saint Benedict formed his first monastery, before the probable date of the British king Arthur, Nestorian sees existed at Nishapur and Tus in Khurasan, in northeastern Persia, and at Rai. Before England had its first archbishop of Canterbury—possibly before Canterbury had a Christian church—the Nestorian church already had metropolitans at Merv and Herat, in the modern nations of (respectively) Turkmenistan and Afghanistan, and churches were operating in Sri Lanka and Malabar. Before Good King Wenceslas ruled a Christian Bohemia, before Poland was Catholic, the Nestorian sees of Bukhara, Samarkand, and Patna all achieved metropolitan status. Our common mental maps of Christian history omit a thousand years of that story, and several million square miles of territory.”

Woof. That is quite an accomplishment.

Now. I should probably say why we’re talking about the Church of the East.

We are talking about the Church of the East for several reasons. First, it illustrates the depth of the problem: The Church of the East was a major force in Christian history for well over a thousand years and yet most people have never heard of it. Second, it highlights the danger of our situation: Most people have never heard of the Church of the East because it was all but successfully annihilated. But most importantly, we’re talking about the Church of the East to clarify an essential point: Though Christianity shaped the West, Christian history is not Western History. It is World History.

Most people do not know that and most empires do not want you to know that.

Do you remember Prince Caspian from Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia? It’s a wonderful story, and it begins in a disenchanted Narnia: The fauns and dryads and talking beasts are gone, and the new regime, called the Telmarines, scoffs and calls them legends. Even so, one of those legends—a half-dwarf named Dr. Cornelius—manages to get through to the young prince Caspian. In a watchtower at night, Dr. Cornelius reveals to Caspian the secret history of Narnia:

“All you have heard about Old Narnia is true. It is not the land of Men. It is the country of Aslan, the country of the Waking Trees and Visible Naiads, of Fauns and Satyrs, of Dwarfs and Giants, of the gods and the Centaurs, of Talking Beasts. It was against these that the first Caspian fought. It is you Telmarines who silenced the beasts and the trees and the fountains, and who killed and drove away the Dwarfs and Fauns, and are now trying to cover up even the memory of them. The King does not allow them to be spoken of.”

That, friends, is exactly like the present situation.

The history of humanity from the time of Christ is not the history of empires and human ascendancy—it is not the history of Yuval Harari or the bombastic New Atheists. It is the history of saints and angels, demons and sorcerers, and, more than anything else, it is the history of the reconciliation of all things to the Father through the son. Christianity has washed the world in one age after another like the first waves of an ever-rising tide.

And yet even so humanity has opposed that story.

Our empires have killed the saints and murdered the prophets and burned the monasteries to the ground. Ani, the city of a thousand cathedrals, is silent, and the old universities of Baghdad are a long time gone. Now, the World and the Flesh and the Devil are trying to cover up even the memory of them.

Believe me, the current government of China does not want it to be known that Christian seeds lie deeply buried in the national soil any more than Western humanists want it to be known that when they teach universal human dignity they are borrowing from the revelations of the Jews and Jesus Christ. The great Muslim powers do not like to discuss their early exchanges with and gleanings from Christianity anymore than the Buddhists do, though it is a fact both systems are deeply indebted to Christianity.

(Note: The debt is very great; I think it would make an interesting series on its own. Here are a few examples: In 782 AD a Bishop named Adam helped Buddhist monks translate sutras from Sanskrit into Chinese, importing, many believe, Christian ideas into the texts. Those sutras founded two schools of Buddhism—Shingon and Tendai—which in turn gave birth to Zen and Pure Land Buddhism. Also, some scholars think that Buddhist monasteries gleaned a large part of their practice from Nestorian monasteries. The influence of Christianity—and Eastern Christianity in particular—on Islam is extensive. You have Ramadan originating in Lent, prayers and prostrations coming via the Church of the East, the veneration of holy sites and heroes of the faith stemming from Christian practice. There are whole books on the topic and they do not exhaust the examples.)

Ever since the Roman soldiers were told to lie about a stolen body (Matthew 28:13-15) the powers of the world have worked very hard to hide the truth.

But they have not succeeded so far and they are not succeeding now.

At least, not quite.

Part III: Resurgence

In 2009, when Thomas Nelson rolled out its Ancient Practices series, the editors rightly observed, “There is a hunger in every heart for connection, primitive and raw, to God. To satisfy it, many are beginning to explore traditional spiritual disciplines used for centuries.”

Ten years before that, in 2001, the avowedly ecumenical Ancient Christian Commentaries on Scripture series appeared, and its editors saw something similar: “Lay readers are asking how they might study sacred texts under the instruction of the great minds of the ancient Church.”

Around the same time an endorsement called Phyllis Tickle’s The Divine Hours “A welcome remedy for the increasing number of lay Christians who have rediscovered the daily offices” and the Wheaton Center for Early Christian Studies, established in 2009, claimed “Early Christianity is the most fertile source of theological reflection and spiritual renewal after the Bible…The early church continues to attract interest across Christian traditions for how it embodied intellectual creativity, spiritual vitality, and concrete action in the midst of great social and political change.”

Apparently, by the turn of the millennium, Christian institutions had begun to observe a real hunger for the past.

Where that came from is an interesting story. If I had to pick a turning point or two in the popular study of early Christianity, I would peg Vatican II and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. At Vatican II it was agreed that Roman Catholics should practice ressourcement, or a return to authoritative sources; after the dissolution of the Soviet Union the Orthodox Church was all but launched into the West.

But the fact is that an interest in the old things can probably be traced to the death throes of the Modern Period—in particular, the orgiastic violence of the Great War.

Right now there is a widespread pessimism regarding the future and so it is hard for us to comprehend the enthusiasm that charged Western Civilization for almost 300 years. But it was a thing. The poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, at the beginning of the 20th century, wrote, “We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched with a new form of beauty, the beauty of speed. A race-automobile adorned with great pipes like serpents with éxplosive breath...a race-automobile which seems to rush over exploding powder is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

He meant it, friends. And he didn’t stop there.

“We are on the extreme promontory of ages!” Marinetti concluded, “Why look back since we must break down the mysterious doors of Impossibility? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the Absolute for we have already created the omnipresent eternal speed.”

Suffice it to say that extreme promontory of ages didn’t pan out. Instead, humanity experienced the most violent century in its history, and that’s pretty extraordinary for a people whose history includes Napoleon, the khanates, and the Assyrian empire. The violence of the 20th century dispelled many people of their illusions. As a result, theologians in particular widened their gaze.

The scholar Brian Daley, describing the education of Hans Urs von Balthasar, notes that by 1934, a contagious interest in the Church Fathers was growing in the Catholic academy: “The study of the Fathers offered a new approach to the mystery of Christian salvation, as it is contained in the word of Scripture and the living tradition of the Church: a way largely free of the rigid intellectual confines of the scholasticism of twentieth-century theological manuals, more self-consciously rooted in biblical proclamation and liturgical practice and more optimistic about the possibilities of a direct, experiential union of the human subject with the infinite God.”

It is interesting that in returning to the Fathers the theologians of the 20th century were recovering the original instincts of Christian scholarship. According to the editors of the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, “Preaching at the end of the first millennium focused primarily on the text of Scripture as understood by the earlier esteemed tradition of comment, largely converging on those writers that best reflected classic Christian consensual thinking.”

What did John Chrysostom have to say about this? is what people used to ask. What did Ishodad of Merv think?

Fortunately for us, people are saying that now.

It’s not just that the pastors I listen to are quoting the Fathers; it’s that Church history is making forays into popular Christianity. The Lutheran rapper FLAME gave us this wonder of an album engaging Church history and the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist; Francis Chan got slightly skewered on the internet for reading Church History and saying the same thing. I mean, not to say that Relevant Magazine isn’t on the cutting edge, but when they post articles on learning to pray from Antony of the Desert, you know something’s close to the tipping point.

By the way: There’s another thing stoking a renewal of interest in early Christian things.

It’s the crude but nonetheless efficient effort of our modern empires to reinvent world history. There are, right now, dozens of well-known initiatives to rewrite history according to the contours of race, gender, and class. I won’t name examples because I don’t care about the individual instances (though some are sillier than others); I care about the impulse. Every time our earthly governments roll out new legislation to govern the study of history, they poke the bear that is Christianity’s vibrant minority.

And it is a minority. To be honest, I doubt that the sleeping giant that is the Western Church will wake up at all. I fear the most likely outcome is that it will bleed to death in a dream. But I hope not.

But there is a small group within Christianity that is awake. Wide awake, and punching back. I don’t mean political pundits here; I mean deeply rooted disciples of Jesus ready to throw down for the salvation of an age.

You should be one of them.

Part IV: Deep Roots are not Touched by the Frost.

Would you like to know the remarkable thing?

Engage Church history and you will immediately discover a vibrant supernatural world and extraordinary discipleship.

The aforementioned Antony of the Desert fought demons and the contests were so loud some visitors thought he was being mugged. More recently, an unnamed priest in the Blasket Islands performed rites of absolution to the wandering spirit of a murderous woman. Some of the starets of the Orthodox Church lived lives of quiet prayer for decades before opening their doors to disciple whole generations. Genevieve (whose bones French revolutionaries put on trial, condemned, and burned) lived an incredible life of fasting and prayer that came in handy when she had to negotiate with Attila the Hun.

I’m not even scratching the surface here. Christian history is the true history of the world; learn it from Christians and your discipleship to Jesus will benefit in ways you can hardly imagine. More than one significant saint got started reading Christian history—Ignatius of Loyola was one of them.

In this, my encouragement to you is threefold.

First, learn the history of the Church from the Church. It should be clear by now that worldy empires won’t tell you the truth. Here’s the acid test: You know you’ve grasped Church history when you can tell it with Jesus as the main character. In spite of human foibles, in spite of extraordinary errors, in spite of all impediments humans invent, God has moved in history. And He has never stopped moving.

Second, start small.

Acquaint yourself with one father (try Maximus the Confessor!). Read one book. Water From a Deep Well is my go-to starting place. 2000 Years of Charismatic Christianity is also a page-turner. If you want to increase your familiarity with Saints from the Christian tradition, Stories of the Saints is wonderful, as is Drinking From the Hidden Fountain. The bestselling The Lost History of Christianity is a paradigm-shifter, as is Timothy Ware’s classic The Orthodox Church. Start sinking your roots. A little goes a long way.

Third, widen your gaze.

As one of my favorite Christian scholars, Dr. Jerry Sittser, says: “Smart Christians are scavengers.” If you are following Jesus you should appropriate the entire tradition. But, since that is the subject of the final installment in this series, I will leave my associated thoughts for the next post.

To end here, let’s go back to Chinese history and to the Christian seeds that lie there.

We’re in a tight spot.

I’ve said it before, but there are no two ways about it. A 50% reduction in Christian practice across the West is no small thing.

Even so, survival strikes me as kind of a lame goal.

Revival seems better.

And that takes us back to those Christians in China.

In 451 AD an Archbishop named Nestorius was condemned as a heretic and cast out of the Christian fold. The Church of the East went with him. Now, more than 1,500 years later, many scholars think that Nestorius was more, rather than less, theologically orthodox, and that the apparent differences in his Christology were differences of dialect and preference rather than differences of doctrine. If that’s so, I cannot help but think God is doing something extraordinary: in our time we might see one of the defining rifts in Christianity actually mended. The East-West schism of 1054 AD gets all the press but the casting away of the Church of the East was older and probably more significant. Might God be healing that wound? If so, what else might God be doing? He’s clearly moving—how else do you account for the sudden appearance of the Orthodox Church in the West? Or for Byzantine Catholicism finding itself—in the likes of Pints With Aquinas host Matt Fradd—center stage?

Something is happening. Reenchantment, renewed discipleship, and a renewed interest in history point to something beyond themselves.

What we may see I must admit I hardly dare to hope for, but if it happens it will be unmistakable, because it has happened before. There are a few moments in Church history that are so extraordinary they earn a special title.

And that, friends, is the subject of the final installment of this series.

Who would have thought gardening could be so much fun and that digging up buried shit could release such a fragrant aroma! I shall return to my Augustine with relish.

I love this—so fascinating. For years I’ve wondered wistfully what our Christianity would look like (and smell like and sound like) if it had come round the globe to us via the East rather than the West—and also so long for the nations of Asia to reclaim their rightful birthplace in the family of Christ as long-time predecessors and ancestors to us, rather than the narrative that they have to conform to a western/white religion.

I also see so much wisdom that echoes Christ in Confucius, dialectics, filial piety, and a communal, honor/shame culture undergirding Chinese culture…not to mention how so many Chinese characters tell Bible stories, being pictorial.

Thanks for writing! :)